Uttarakhand HC stays panchayat polls over rotation of reservations.

The Uttarakhand High Court’s 24 June 2025 order froze the forthcoming panchayat elections because the State tried to reset the statutory “rotation” of reserved seats midway—a move the Bench said violated earlier court directions and the constitutional rule in Article 243-D that the same ward cannot remain reserved repeatedly. The episode is an excellent entry point to revise three static pillars: (i) Part IX & IX-A (Articles 243–243 O / 243 P-243 ZG) that constitutionalise rural- and urban-local bodies, (ii) the 73rd & 74th Amendments’ reservation-and-rotation architecture, and (iii) the Basic-Structure doctrine’s protection of grass-roots democracy. Details follow.

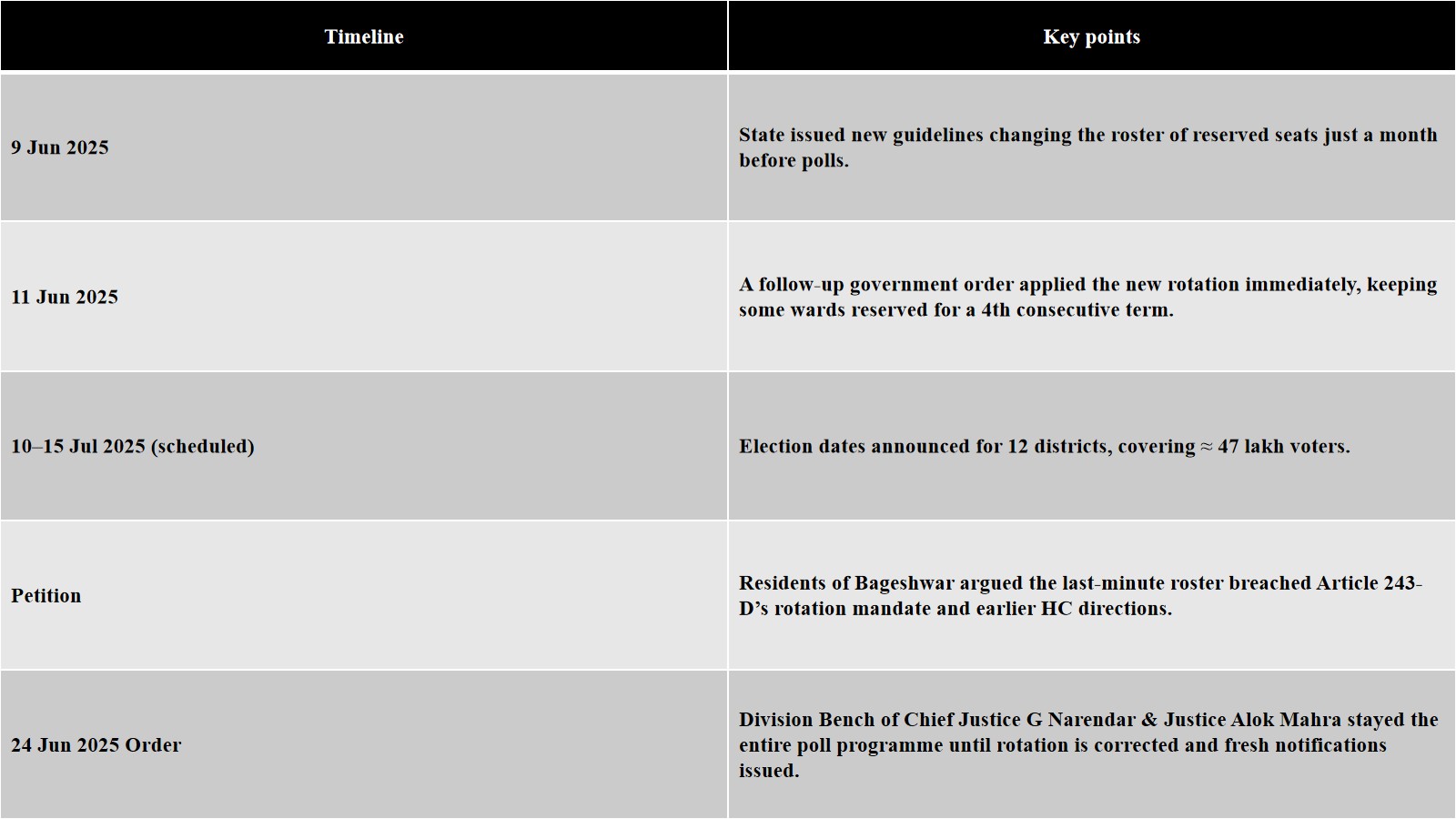

What exactly did the Uttarakhand High Court stop—and why?

Court’s reasoning (simplified):

-

Rule of rotation—every five-year cycle a reserved seat should shift, ensuring opportunity for all communities. constitutionofindia.net

-

Re-reserving the same wards curtails the electoral rights of aspirants from other categories, violating equality and the democratic mandate of Part IX.

-

Election integrity is part of the basic structure; therefore even State policy goals cannot trump the rotation principle.

Why does the Constitution insist on “reservation by rotation”?

Text of Article 243-D (Panchayats)

-

Sub-clauses (1)–(3) reserve seats for SC/ST & women “and such seats may be allotted by rotation” to different constituencies. constitutionofindia.net

-

Sub-clause (4) extends the same idea to the offices of Chairpersons.

-

Similar wording exists for Municipalities in Article 243-T.

Purpose: prevent “permanent reservation” of a single ward; spread leadership experience and social justice benefits across the territory.

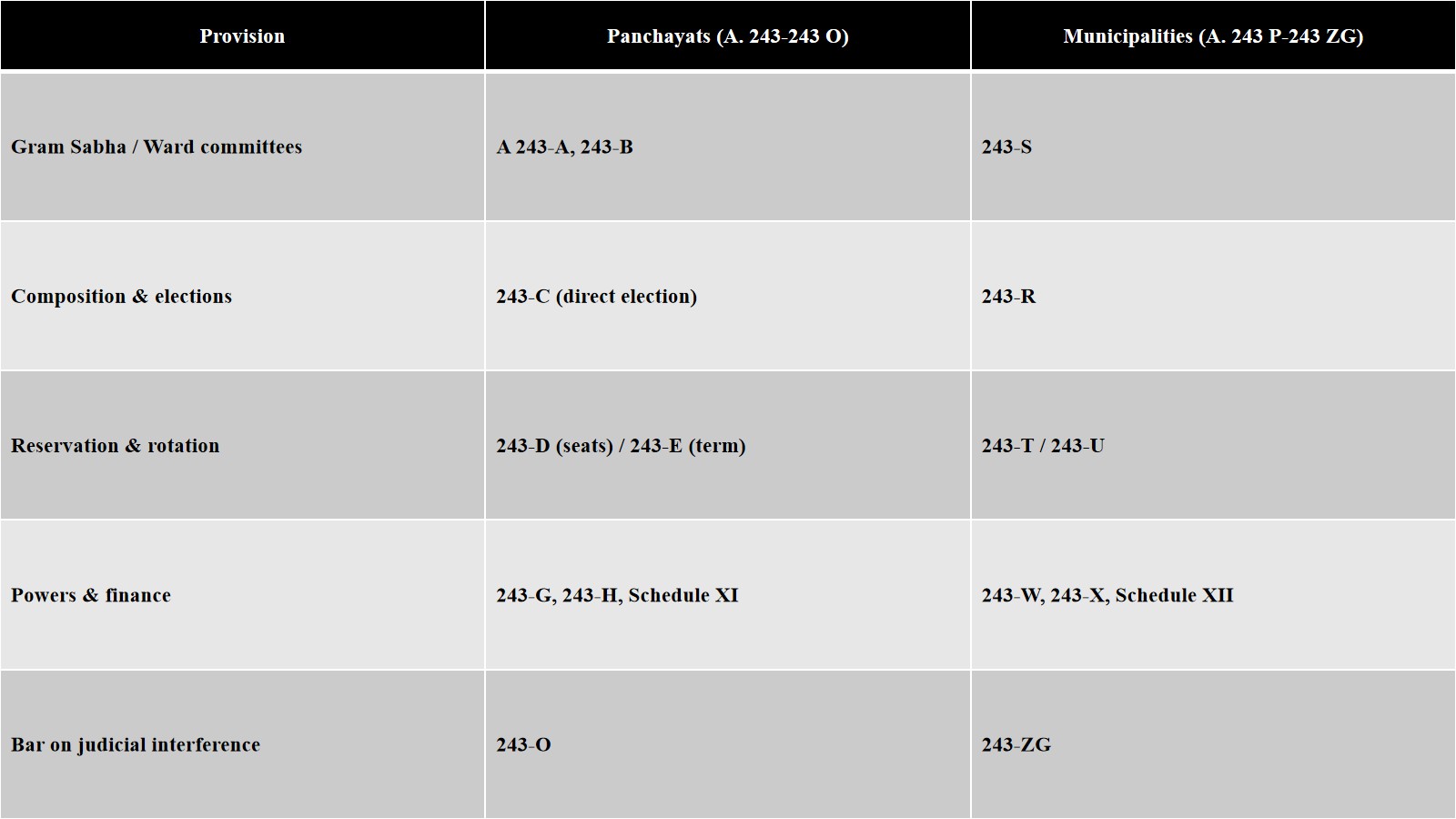

Static core unpacked

Part IX (Rural Local-Bodies) & Part IX-A (Urban)

These Parts were inserted by the 73rd (1992) and 74th (1992) Amendments, bringing ≈ 2.5-lakh panchayats and 4,500 urban bodies under a uniform constitutional umbrella.

Reservation rules & the rotation principle

-

Quantum – seats for SC/ST proportional to their population; ≥ 1/3 of all seats for women, cutting across categories.

-

Rotation cycle – Constitution leaves the periodicity to state law but intent is “every election”; most state rules follow a five-year cycle, e.g., Karnataka’s 1998 Rules and Tamil Nadu’s 1995 Rules.

-

Offices of Chairpersons must also rotate, preventing capture of key posts by one group. constitutionofindia.net

-

Judicial enforcement: Supreme Court in Kishan Singh Tomar v. Municipal Corp. Ahmedabad (2006) held that timely elections and adherence to Article 243-U/T are non-negotiable.

Local-body democracy & the Basic-Structure doctrine

-

Basic structure (Kesavananda, 1973) declares democracy an unamendable core.

-

73rd/74th Amendments deepen democracy by making “institutionalised decentralisation” constitutionally protected; scholars and courts now treat effective self-government as flowing from the basic structure.

-

Delayed or manipulated local-body elections therefore offend both Article 243 and the broader basic-structure guarantee, giving High Courts authority to intervene despite the bar in 243-O/243-ZG if the process itself is undermined.

Key takeaways for UPSC answers

-

Quote the article – “seats may be allotted by rotation” (A 243-D (1) & (3)); remember similar text in A 243-T.

-

Explain the logic – rotation ensures distributive justice, leadership diffusion and checks “seat capture.”

-

Link to case-law – Kishan Singh Tomar (SC, 2006) + Uttarakhand HC (2025) illustrate judicial protection of the rotation rule.

-

Basic-structure angle – show how grass-roots elections operationalise the democratic core; any executive shortcut faces strict scrutiny.

-

Integrate both Parts – whenever a question mentions panchayats, also reference municipalities (and vice-versa) to demonstrate holistic grasp.