Megalithic burial practices of peninsular India & archaeological methods – with a focus on recent skeletal finds from coastal Karnataka

Megaliths are among the clearest fingerprints the Iron-Age peoples of peninsular India left on the landscape. This essay unpacks their chronology, geography, architecture, grave goods, economy, beliefs and the scientific tool-kit that is now rewriting their story—before zooming in on the newly documented rock-cut burials and skeletal material from coastal Karnataka. Along the way it shows how modern methods such as AMS-¹⁴C, isotopes, aDNA and drone-LiDAR are turning what used to be a culture-historical puzzle into a laboratory for hard science and holistic social history.

Chronological & Cultural Frame

South-Indian megalithic activity spans roughly 1200 BCE – 200 CE, bridging the Late Neolithic and Early Historic phases. Radiocarbon assays from Vidarbha tooth-enamel anchor some burials between AD 250-874, reminding us that the practice lingered into early medieval times. Typologically and technologically, the horizon coincides with the first mass use of iron implements in peninsular India, documented in metallographic studies of smelting slags from megalithic levels in the Deccan.

Spatial Distribution & Key Necropoleis

Megaliths concentrate in four belts:

-

Northern Karnataka – Andhra eastern Deccan: Iron-rich lateritic plateaus around Brahmagiri and Maski.

-

Central Karnataka – Koppal district: the vast dolmen necropolis of Hire Benkal with c 1 000 monuments, now on UNESCO’s Tentative List.

-

Tamil Nadu littoral: Urn-fields of Adichanallur, where 3 000-year-old skeletons lie exhibited in situ.

-

Coastal Karnataka & Kerala: Rock-cut cave burials at Ramakunja, Mudu Konaje and Udupi-Dakshina Kannada, including the 2022 “zero-circle” sepulchre and 2023 terracotta-figurine dolmens.

These sites hug ore belts, river valleys and ancient littoral trade routes—explaining both the spread of iron technology and the visibility of exotic grave goods.

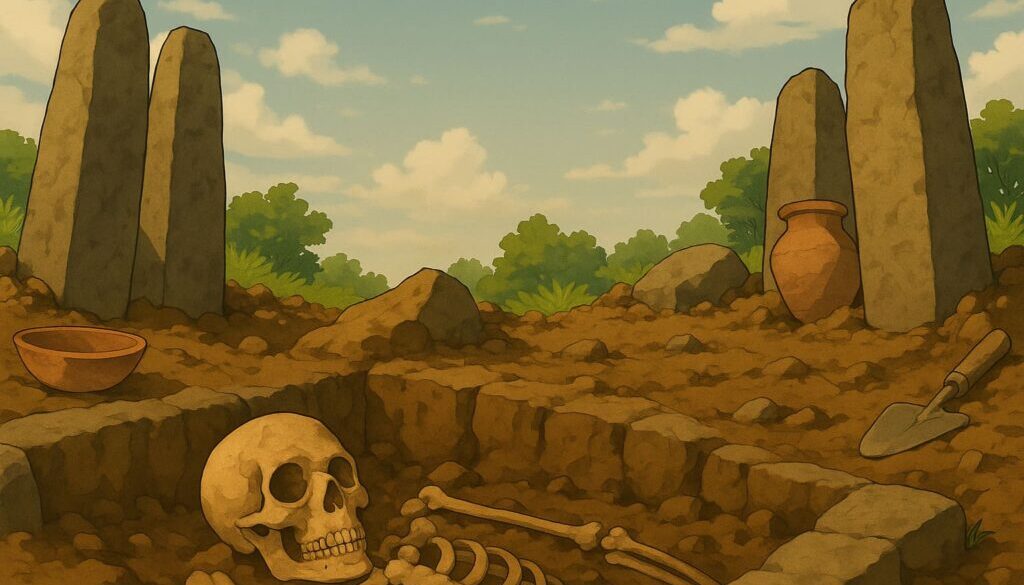

Architecture of Death: Forms & Construction

Peninsular India showcases the world’s richest array of megalithic architectures—

dolmens, dolmenoid cists, cairn-circles, menhirs, pit-urns and laterite-cave chambers.

Hire Benkal’s “dwarf chambers”—dolmens scarcely a metre high—are built of local granitic gneiss and arranged along a notional street, giving the necropolis the eerie look of a deserted stone village.

In the wetter coastal belt, masons sliced burial cells horizontally into laterite scarps; the Ramakunja tomb displays a 7-ft engraved circle on the roof slab, directly above a hemispherical chamber—the first such ‘zero-marker’ recorded in India.

Grave Goods & Social Signals

Classic assemblages mix Black-and-Red Ware, Russet-Coated Painted Ware, iron weapons, copper or bronze ornaments and semi-precious bead strings.

Carnelian and glass beads link the tombs to wider Indian-Ocean commerce; etched carnelian blanks identical to those in Harappan workshops surface even today in Kerala excavation pits, while a recent bead-study from Pattanam demonstrates continuous lapidary traditions into the Early Historic era.

Terracotta figurines—mother-goddess, bovines, peacocks—found inside the Mudu Konaje dolmens reveal an ideological repertoire tied to the Bhoota/Daiva cults of coastal Karnataka.

Subsistence & Economy Behind the Monuments

Isotopic signatures (δ¹³C, δ¹⁸O) in equine tooth enamel from Vidarbha burials point to a C-4 dominated diet and semi-arid hydro-climates, corroborating archaeobotanical finds of millets and pulses. Combined with iron sickles, plough-shares and pastoral bone spectra, the data argue for mixed farming-pastoral economies with specialized iron-production niches.

Belief, Ritual and Community Structure

Circular cairns and menhirs often align to cardinal points, hinting at cosmological ordering, while secondary burials and collective ossuaries suggest ancestor veneration. The terracotta mother-goddess figurines align with folk fertility cults, bridging prehistoric and living ritual systems on the western coast. Parallels in Sri Lankan jar burials and Southeast-Asian cave urns reinforce theories of Indian-Ocean interaction spheres.

Scientific Tool-Kit: From Spades to Spectrometers

Fieldwork in Coastal Karnataka: A Case-Study

Recent seasons focused on the lateritic hillocks between Udupi and Dakshina Kannada:

-

Ramakunja sepulchre—a rock-cut burial marked uniquely by an engraved zero symbol, chamber oriented NE, yielding BRW sherds but no grave goods; soil micromorphology suggests secondary fill episodes.

-

Mudu Konaje dolmen cluster—eight figurines plus bone splinters and an iron knife from collapsible dolmens dated c. 800-700 BCE via stylistic seriation.

-

Udupi laterite-caves survey mapped 22 new features; preliminary GPR slices indicate intact chambers under collapsed roofs, guiding future conservation trenches.

Challenges include salt-laden humidity that accelerates bone decay, and rapid land-use change; hence protocols now mandate on-site consolidation and community-heritage agreements under the AMASR (1958) framework.

Comparative & Global Insights

Architecturally, Indian dolmens echo Atlantic Europe’s passage graves yet differ in their Iron-Age dating and inclusion of iron artefacts. Rock-cut caves resemble Kerala–Sri Lanka coffin caves, while bead-based exchange networks link the megalithic Deccan to Arabia and the Mediterranean—showing that South-Asian burials sat within a pan-Eurasian Iron-Age interaction web.

Historiography & Research Frontiers

From Wheeler’s 1947 Brahmagiri trenches to UNESCO’s 2021 Hire Benkal nomination, scholarship has moved from typology to science-driven social archaeology. Upcoming priorities include:

-

Full genomic sampling once legislation opens curated skeletal collections.

-

High-resolution LiDAR of laterite landscapes before urban sprawl.

-

Integrated palaeodiet and palaeoclimate modelling across coastal-interior transects.

Takeaways for UPSC Aspirants

-

Inter-link static and dynamic: marry textbook typology with the latest dating breakthroughs.

-

Use maps & diagrams: mark four megasites, illustrate a dolmen cross-section with grave assemblage.

-

Quote methods: citing AMS, OSL or LiDAR instantly raises answer quality in Mains GS-I or optionals.

-

Relate to heritage policy: reference AMASR Act provisions and UNESCO Tentative status when discussing conservation.

With robust science now illuminating beliefs, economy and connectivity, megalithic burials are no longer mute stones but vivid voices of India’s Iron-Age society—a theme that UPSC examiners increasingly test for its perfect blend of culture, science and governance.