Judicial review of welfare-scheme nomenclature & the doctrine of separation of powers

India’s Constitution gives the State wide latitude to roll out welfare schemes, yet it also equips the courts with an equally strong power of supervision. Over five decades, the Supreme Court has refined a coherent framework for testing whether the way a programme is branded or publicised trespasses the limits of executive or legislative power. The core standards emerge from Article 13 and the basic-structure doctrine, are sharpened by canons such as colourable legislation and proportionality, and are applied through a line of rulings from Kesavananda Bharati (1973) to the Court’s 6 August 2025 decision lifting the Madras High Court’s ban on Tamil Nadu’s “Ungaludan Stalin” scheme. This article maps that terrain, showing how the doctrine of separation of powers remains the lodestar for judicial scrutiny of welfare-scheme nomenclature.

Constitutional Foundations

Judicial review and Article 13

Article 13 empowers courts to strike down “laws” (a term that includes executive orders and schemes) inconsistent with Part III rights, making judicial review itself part of the Constitution’s basic structure. By 1973 the Court had ruled in Kesavananda Bharati that any amendment abolishing this review would be void, entrenching separation of powers as an immutable feature.

Executive competence and federal balance

Articles 73 & 162 define Union and State executive power; read with the Seventh Schedule they decide who may launch or rename a scheme. Article 246 builds a federal “water-tight compartments” test; naming a Union-funded scheme after a State leader (or vice-versa) can thus trigger pith-and-substance review.

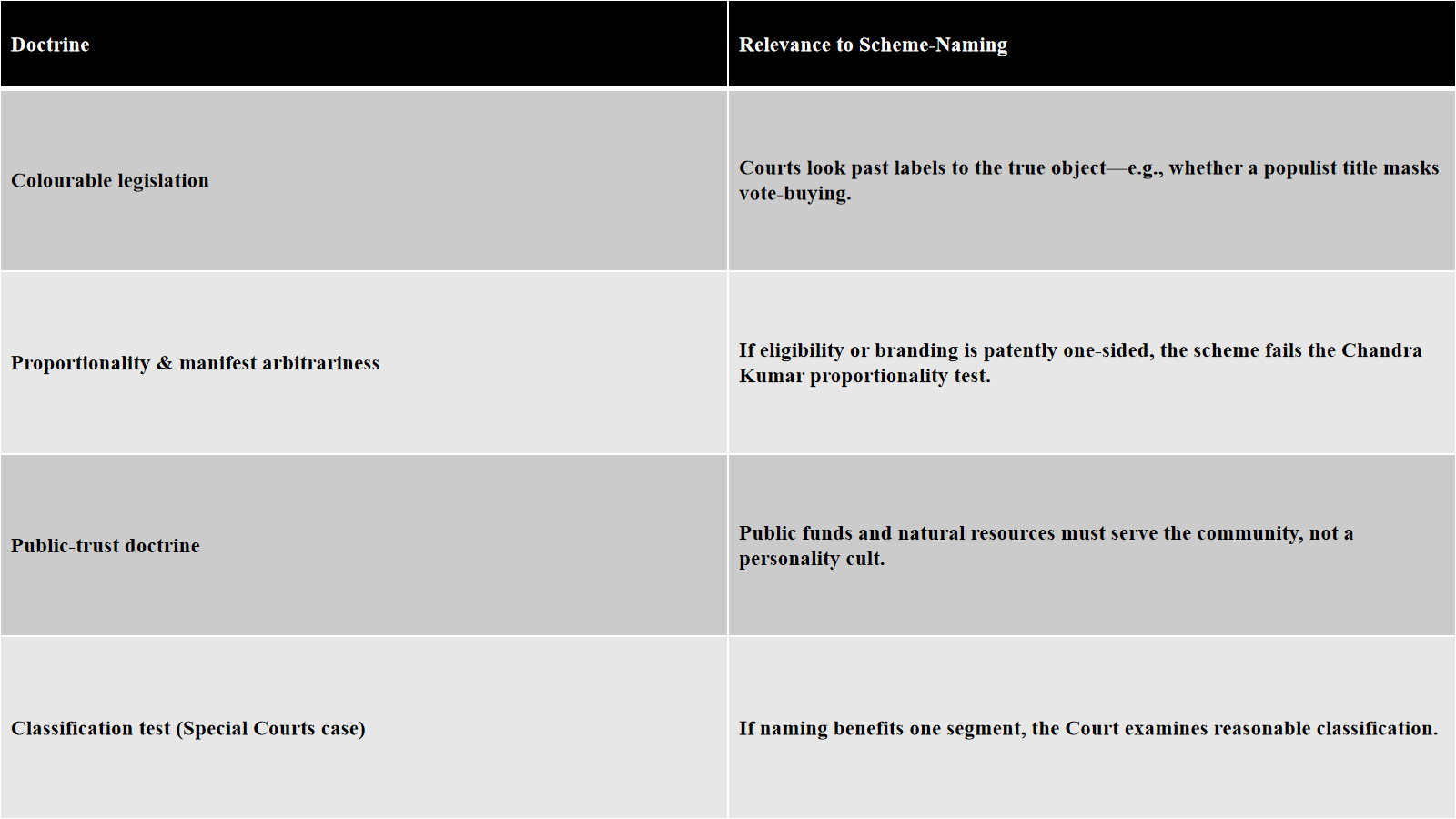

Key Doctrinal Tools

Landmark Case Trail

-

Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) – Cemented separation of powers and the inalienability of judicial review.

-

In re Special Courts Bill (1979) – Laid down five-point test for determining legislative competence and reasonable classification, later used to check special-purpose welfare laws.

-

S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994) – Flagged misuse of executive power for partisan ends; provides analogy for partisan branding of schemes.

-

Common Cause v. Union of India (2015) – Prohibited photographs of political leaders in taxpayer-funded ads, permitting only certain constitutional functionaries; laid normative basis for today’s disputes.

-

BALCO Employees Union v. Union of India (2002) – Asserted “judicial restraint” in economic policy, a counter-weight reminding courts not to micromanage fiscal choices behind schemes.

-

Madras HC interim order (31 July 2025) – Barred use of living leaders’ names; first instance court relied heavily on Common Cause.

-

Supreme Court order, 6 Aug 2025 – Set aside the above ban, holding that naming programmes after leaders per se is not illegal and criticising “selective targeting.”

The Election Commission’s Parallel Discipline

During an election period the Model Code of Conduct (MCC) bans government ads that exalt political personalities. Several High Courts invoke these MCC clauses even between elections, but the Supreme Court clarified in 2025 that MCC restrictions cannot be stretched into a general constitutional prohibition on scheme names.

Separation-of-Powers Diagnostics

When can courts intervene?

-

Illicit purpose – If evidence shows a scheme’s nomenclature is a colourable device to influence voters mid-poll, judicial invalidation is likely.

-

Competence breach – A Union-branded scheme delivering a State list subject without concurrence violates Articles 246–254 and is ultra vires.

-

Discriminatory branding – Schemes singling out one community or region may offend Articles 14/15.

When will courts defer?

-

Policy realm – Following BALCO, fiscal-design questions (amount of subsidy, delivery mode) are “non-justiciable” unless patently arbitrary.

-

Pan-Indian practice – The 2025 ruling noted that almost every government, Centre included, uses leader names; selective litigation can be dismissed with costs.

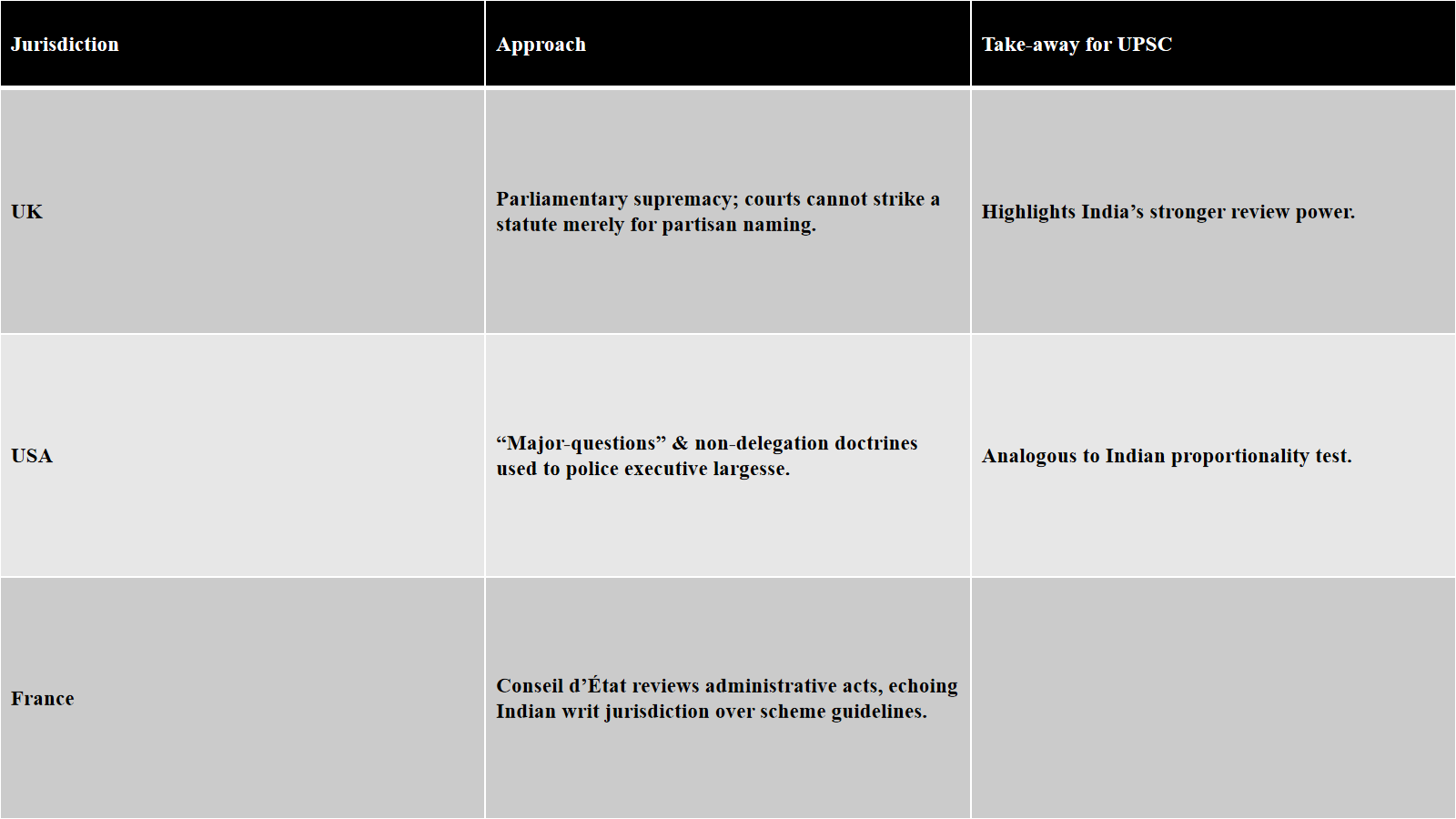

Comparative & Theoretical Perspectives